NOTE: The opinions expressed here are those of the author only and are not intended as medical advice. Please check all claims independently, and consult a healthcare professional before taking any health-related action.

When I was little, I was afraid there was a monster under my bed whose hand would reach out and grab my leg when I was coming back from the bathroom in the middle of the night.

Sometimes I was so scared I’d climb in bed with my parents downstairs.

Finally one night, my dad patiently took me back up to my room, turned on the lights, even got a flashlight and lit up the dusty floor under the bed for me. “See, no monster.”

That satisfied my thinking, rational brain.

I grew up, of course. And now I know there’s nothing under my bed but yoga mats and camera tripods.

Still, some nights when I’m feeling particularly spooked, to this day, I will approach that vague shape of the bed in the dark and will launch myself into it from as far away as I can get to avoid that scary hand on my leg.

Those are the times when I’m controlled by the primitive part of my brain that no amount of “evidence” can reach.

The “Monster Under the Bed” series

This series of six articles speaks to our adult, rational brains, exposing the more manageable threat posed by four of the scariest diseases we can imagine, plus some we typically don’t think of.

The facts still don’t keep my primitive brain from fearing the hand reaching out from under the bed in the darkness.

Neither will these insights about diseases completely quiet those primitive fear reflexes in all of us that can be triggered by the specter of an alleged “deadly disease” or pandemic.

But perhaps by shining the light of knowledge onto those “monsters under the bed” we’ll be better able to tame that spooked inner child when someone tries to use fear to make us do things we wouldn’t ordinarily go along with.

Our cast of monsters: a preview

In this series, we’ll first talk about four of the ugliest of monsters our minds can conjure up to feed our fears:

Plague/bubonic plague/Black Death

Smallpox

Spanish Flu

Polio

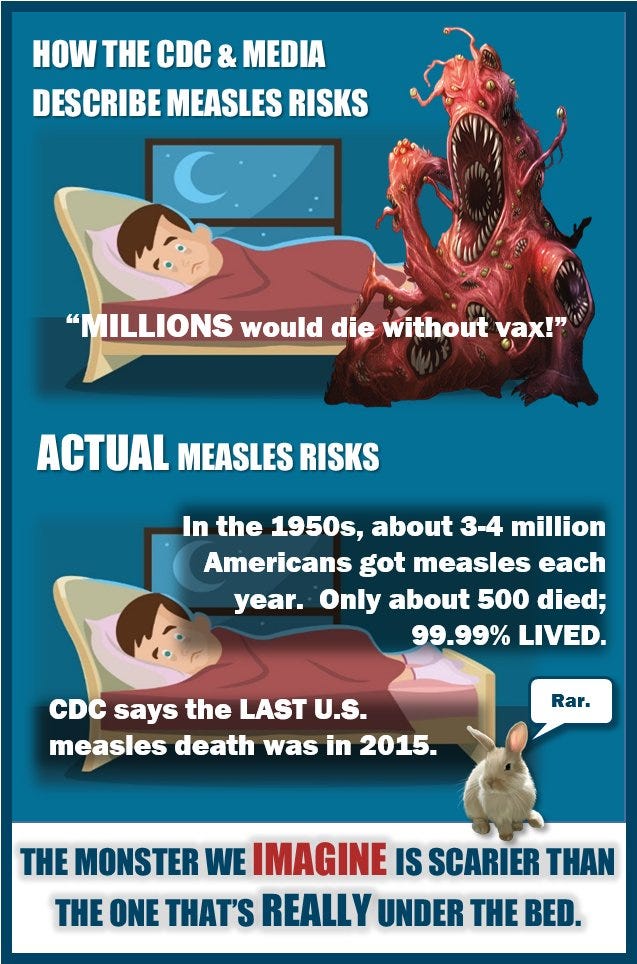

(BTW, measles is such a relative lightweight it didn’t even make the quarterfinals. Though we’ll talk about it in Part 6.)

Plague

Plague and bubonic plague were also called Black Death, a disease so scary it needed a proper name with capital letters. These are all names for the same thing.

Most prevalent in the mid-1300s, plague was caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis.

It presented itself in three main forms: pneumonic, bubonic, and septicemic.

And it killed between 75 million and 200 million people worldwide. In Europe, it wiped out 30-60% of the population.

Pretty badass, right?

Not really.

Today, the US still sees a dozen or so cases each year. It’s just anther (yawn) bacterial infection, with good or bad odds depending on how it’s handled and the patient’s overall health.

Survival rate? About 95% or better with prompt diagnosis and antibiotics.

Smallpox

Back in 2001, shortly after the 9/11 attacks, we heard rumors from the media and government that smallpox might be released from a biolab and make a deadly comeback.

Like plague, the mere mention of smallpox still sends a chill up our spines. Not because we’ve ever seen anybody who had it, but because of stories we’ve been told about it all our lives.

It’s hard to pin down how many deaths smallpox caused. Some estimates say a half-billion died in the last 100 years of its existence. That comes to about 5 million deaths per year worldwide in its heyday.

But writers from early times report multiple other factors that actually led to those deaths. (People died “with” smallpox, not “of” smallpox. Sound familiar?)

Many of those doctors wrote that smallpox was a minor infection that could be easily managed.

More likely it was the treatments, and crude, contaminated vaccinations that contributed to the alleged smallpox deaths, rather than the disease itself.

Spanish Flu

This bad boy, caused by the H1N1 virus (a predecessor to what would later be called “swine flu”), killed some 50 million globally in 1918-1919.

However, fewer than one million (675,000) died in the US.

So although it was bad, we can’t technically say, “flu vaccines would have saved millions,” in the US at least. (And certainly not with modern flu vaccine effectiveness measured in the wimpy 30-40% range.)

What really happened in the pandemic is a complicated story.

For example: Imagine what you would do if you went to your doctor to manage the flu and he told you, “Take a half-bottle of aspirin twice a day and call me in the morning.”

Now imagine doctors in military wards in 1918 prescribing that very treatment.

Couple that with secondary bacterial pneumonia complications treated with toxic standard protocols that included the use of strychnine, a poison, and you’re throwing a boat anchor on a downing man.

Undoubtedly, something killed millions of people during the Spanish Flu pandemic. But was it the flu? Or was it something else?

Polio

Even those who would rather avoid vaccines or are willing to let people make their own decisions about vaccination will say, “But what about polio?”

Maybe they know somebody or heard a story about a relative or a friend who was permanently crippled from polio. Still limps to this day.

Surely, we at least need just this one little vaccination, right?

Not necessarily.

Far less deadly than the others on this list, the polio monster is better known for its widespread crippling of children.

But the facts tell a different story.

1. Poliovirus causes a relatively mild intestinal infection that most of us today could’ve had and blown off as nothing more than a transient “stomach bug.”

2. Pesticides that used arsenic and lead were sprayed on food crops about the time the so-called “polio” epidemic began. When ingested, these toxic heavy metals caused paralysis and crippling that looked just like polio.

3. A clever re-definition trick right around the time the first polio vaccines hit the market shifted many cases of paralysis from the counts of “polio cases” into a variety of other crippling disease categories. This reduced the number polio cases virtually overnight, without counting vaccine effects.

4. The mainstream treatments for polio paralysis at the time actually prevented recovery and led to those permanent remnants of crippling we see or remember in older generations.

5. Oh, and the polio vaccines themselves actually can cause polio.

So while polio, like the other monsters here, should never be taken lightly, it has really gotten a lot of bad press it didn’t deserve.

It’s time we corrected the record about all these critters.

And just how scary they really are.

Next up – MONSTER 1: Plague

This INTRO has given you a brief overview of the relative scariness of each of the monsters that those who profit from illness and fear might use to send us shrinking back into our spooked-child state of mind.

MONSTER 1 will dive deeper into Yersinia pestis and the plagues it has caused.

And, like every part of the series, it questions whether the fear we attach to this particular monster is justified in modern places and modern times.

See you next time.